Patanjali and the Yoga Sutras

Patanjali was born in Gonarda (now known as Gonda) in northern India. Unfortunately, not many facts are known about his life.

One known fact is that Patanjali studied Yoga with the great yogi, Nandhi Deva, Muni, Vyaghrapada and Thirumoolar.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are widely considered to be one of the best instructional books on yoga.

Patanjali divided the Yoga Sutras into 4 sections, or Padas.

The first section, Samadhi Pada, contains 51 sutras, or verses, and is focused on the state of Samadhi.

Samadhi is the blissful state of infinite expansion beyond the mind.

In the yoga sutras, Patanjali gives specific details about how to achieve Samadhi and how to recognize the various types and levels of Samadhi. This section is dedicated to advanced spiritual aspirants, and has the sole purpose of triggering enlightenment without practicing.

The second section, known as Sadhana Pada, is the practice section, which contains 55 sutras. Here Patanjali prescribes two types of Yoga: Kriya Yoga (the Yoga of Action) and Ashtanga Yoga (Eightfold Yoga), also known as Raja Yoga.

“TAPAH-SVADHYAYESVARA-PRANIDHANANI KRIYA-YOGAH”

~ Sadhana Pada, Verse1

Translation – Austerity, Self-study and dedication to the Highest, comprises the preface of Kriya yoga.

Patanjali did not go in to much detail when describing Kriya Yoga and this may leave us in the dark with infinite possibilities of varied interpretations. In my opinion kriya yoga for him had to do with austerities such as fasting, cleansing the physical body with shat karmas and so on. When he refers to self-study, he is simply talking about Self introspection. In other words he directs the practitioner to understand who he/she really are in the midst of action (practices and daily life) by observing his/her interior constantly.

Ashtanga Yoga is an elaborate eight-branched system of interlinking practices, including asanas, pranayama and meditation, each of which support and deepens the expression of each linked method.

Yoga Adityam has a unique perspective on these practices, quite different than what is usually taught elsewhere, and gives them an interpretation you have probably never seen before. The focus of Yoga Adityam is on liberation from the oppressive mind and ego, and uses the methods of Ashtanga Yoga to free the spirit, without adding more repressive concepts.

The eight limbs of Patanjali’s Ashtanga Yoga begin with Yamas, a system of ethical regulations.

The first of the Yamas is:

- Ahimsa – non-violence. We must live in a non-violent way. But how is this to be accomplished?

- In Yoga Adityam, through the practice of yoga nidra (yogic sleep), the practitioners, instead of repressing their instinctual reactions, slowly learn to connect with their innermost nature, which is unconditional love. Through this methodical practice they are gradually enabled to open their hearts, this will awaken in them an all-encompassing compassion for all beings. The result is that ahimsa will flourish naturally.

The next Yamas are:

- Sathya – truthfulness and honesty;

- Asteya – non-stealing; and

- Aparigraha – non-possessiveness.

Regarding these, rather than addressing them in a rule-oriented way, Yoga Adityam endeavors to first uncover the chains that keep the spirit tied down to the ego. Before insisting that practitioners never steal or lie, our practice exposes the greatest mistake of all, which is to believe that we are separate entities, confined to individual bodies. The teaching of Yoga Adityam reveals the numerous ways that the mind uses to perpetuate the false sense of individuality, and exposes how it protects its mind-created holographic identity, the sense of ‘I.’ It is only in defense of this false sense of identity that anyone would ever lie, or steal, or become overly attached to their possessions. By uncovering the deepest source of falsehood within, we are able to cut wrong behaviors at the root, rather than just ineffectively trimming the leaves of wrong actions with moral and fear that will eventually keep growing.

As our practice deepens, we will gradually come to understand that if we lie, or steal, we are doing that to ourselves, or if we are possessive, greedy, aggressive, chronically angry or sad, we are only strengthening the darkness within us – darkness which has the power to destroy every drop of sanity we have.

As we continue we comprehend that there is nothing but the one omnipresent Self.

In reality there is no multiplicity; multiplicity is in fact a mirage. The truth is that there is only one: the all-pervading, infinitely expansive, immortal Self. Once this vision is gained, we will know ourselves to be the Supreme Self, then fear disappears completely. When there is no fear there is no sense of lack,

When we see the Supreme Self in everyone, compassion for all arises7777777777777777777777777777777777777777777.

The list of Yamas concludes with:

- Brahmacharya – celibacy.

Brahmacharya is usually defined as refraining from sexual activity, and this is often interpreted as an instruction to repress sexual energies. In Yoga Adityam we have a very different interpretation of Brahmacharya. The true meaning of Brahmacharya is ‘abiding in Brahman, the Supreme Consciousness.’

The truth is that abiding in Brahman has nothing to do with sexual repression. In Yoga Adityam we do not repress any energy; on the contrary, we set all energies free. As we see it, the sexual force is already repressed by the mind and maintained in the lower two chakras (Muladhara and Swadishtana).

The ego feeds on and extracts much vital power from this area, and we spend a lot of energy defining our sexual identity. This misidentification of our true nature with sexual identity produces “egoic” labels (“I am straight,” “I am gay,” “I am good looking,” “I am unattractive,” etc.), which strengthen the false identity, therefore enabling the mind’s central axis of fear and desire to anchor ever deeper in our hearts, obscuring our true identity, which is limitless Spirit.

By understanding the central point that what we are is the Atman, the limitless Divine Self, and not separate bodies with a particular sexual orientation, we can begin to gradually redirect this precious and powerful energy to the higher spiritual centers. This is not done by repressing sexual energy, but rather by redirecting this energy, so that it becomes fuel for the full revelation of our supremely blissful true nature.

As this new understanding gradually grows through meditation, the practitioners begin to enjoy the new level of pleasure derived from this method of internal alchemy, and cherish the bliss of divinization more than the physical pleasure that sex bestows.

Yogis who have a partner, instead of wasting their energy in a moment of pleasure, will make their energy ascend through the spine (aided by the tantric exercises of Yoga Adityam) and use sexual unity to propel their energy to higher chakras.

Yoga Adityam’s version of Brahmacharya offers a way to freedom from guilt and fear. It is a path to the discovery of our inherent purity. If an egoic sensation of sadness, unworthiness, powerlessness, incapacity or guilt should occur while practicing the Yoga Adityam exercises of sex, practitioners will learn to see the face of the ego in those reactions.

We should not under any circumstances let Brahmacharya, or any other percepts be used by the ego to enhance pride or cause guilt. Nor should we turn precepts into strict rules that if broken would denote a sinful act for which we deserve punishment. Yoga Adityam offers a path to healing from all such damaging concepts. Brahmacharya is simply a way to reestablish the direction of our sexual energy to its original course. Brahmacharya is a way back to the innocence and the full discovery of our inherent divinity.

The Niyamas

After the Yamas, Patanjali names the Niyamas, or personal disciplines:

- Saucha – Transparency of mind.

Saucha means honesty and openness. It means we are not hiding anything. This way of living frees the mind into the great ocean of the expansive Self.

- Santosh – Contentment, or satisfaction.

Contentment is the practice of being happy with what we have in the present moment, rather than constantly seeking more, bigger or better things in the future. We are no longer postponing happiness, but instead learn to discover the peace and joy that are here and now. This will gradually relax the practitioner, and the desires that enchain them will slowly fall away.

Instead of ‘I want peace,’ the practitioner learns to drop the “I”, drop the want, and discover the peace that is already here and now.

- Tapas – Austerities; spiritual practices which generate heat.

According to Yoga Adityam, spiritual practices and austerities should be done by enticing the mind to cooperate rather than by forcing it to obey. We have found that making spiritual practices genuinely fun for yourself is much wiser than trying to beat your mind into submission!

The mind hates routine, and that is why we emphasize that the practitioner be centered in the present moment, and subsequently allow spontaneous inspiration to occur. When we learn to abide in the present moment, everything is new, and each movement is fresh, original and innovative.

- Swadhyaya – Self-study.

In Yoga Adityam, we use this Swadhyaya niyama as a springboard to introspection. Practitioners are guided to go within and review their lives, and by using right thinking and positive thought forms, free themselves from any negative emotional patterns that they may be carrying.

- Ishwari Pranidhana – surrender to God.

Surrendering to God

This is the most highly beneficial step you can take on the spiritual path. When we surrender fully to the Supreme Being, or the Universe, if you prefer, the oppressive ego dies, and we realize that we have always been the infinitely expansive Divine Self that we had been surrendering to.

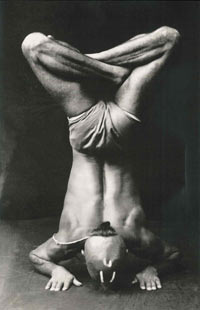

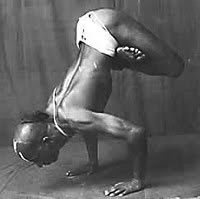

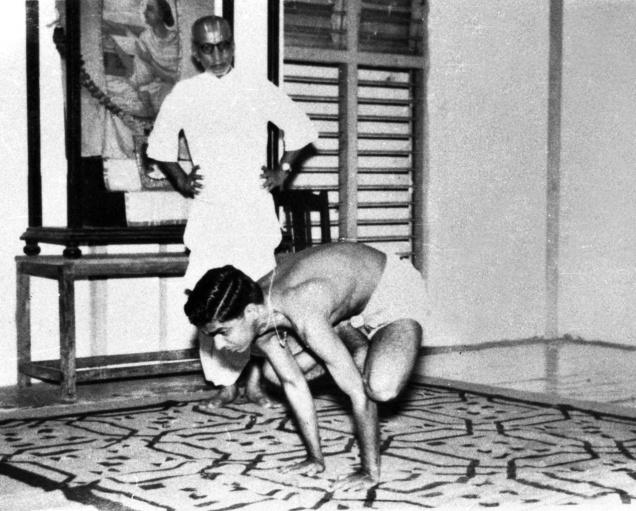

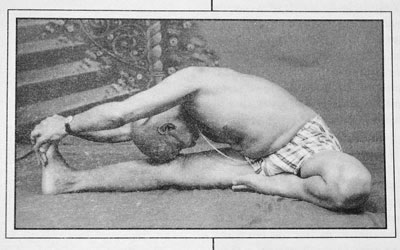

- Asanas– (yogic positions)

“Sthira sukham asanam. (Asanas are steady and comfortable postures.)”

~Patañjali

Asanas are the numerous body positions which yogis use to assist in the achievement of mental symmetry and spiritual expansion. As Patañjali points out, these postures should be pleasant, unwavering and relaxed. While doing asanas we are not trying to control the body, but free it completely. Through complete relaxation on an asana we will be destroying physical, mental, emotional and astral blockages.

- Pranayama– Breathing techniques.

Pranayama means expansion and freedom of breath.

Some translations describe this point as “control of breath”; however if we closely observe, we find that our breath is already controlled and restrained by the ego and our emotions. With Yoga Adityam’s pranayama exercises we can learn how to set our breath free, like a bird soaring through the air.

- Pratyahara– Withdrawal from the senses.

Genuine pratyahara is not a forceful withdrawal from the senses, but rather an abandonment of them, which naturally comes after the understanding that pleasure and pain are inseparable sides of the same coin. The senses, while promising us pleasure, lead us inexorably to pain. When we realize the lack of practical wisdom in pursuing happiness through the senses, we happily abandon that pursuit, and recognize the senses as the deceptive cheats that they are. Once we have mastered our senses, they can become trusted servants that help us live in the present moment, and can therefore serve as a doorway to Enlightenment.

Our mistake lies in being attached to a particular good sensation we once experienced, such as a flavor, an static feeling of some kind that made you feel whole, created because you were in the present moment, so be careful because this craving to repeat old good experiences, and the idea that repeating them will bring real happiness, creates a deceptive mental pattern, in which the mind immediately tends to equates lasting happiness with temporary sensory satisfaction.

This fallacy encloses joy and bliss in the network of time that snatches the soul from the precious present moment, which is the cause of real bliss.

Such patterns of desire seduce the mind into trying to repeat the previous sensations, and this is impossible, since they were felt because you were aligned with the present; going down this route leads only to frustration, addiction and precious time is wasted in pursuit of trying to keep one mirage after another alive.

Once this vicious cycle is understood, pratyahara becomes a joy. We learn to effortlessly drop the senses, and discover the great bliss and peace that lie at the very root of the mind, prior to the ‘I’ that perceives and processes sensory data.

The third Pada in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is called Vibhuti Pada, which contains 56 sutras. Vibhuti means ‘power’ or ‘materialization.’ This Pada begins with descriptions of the final three limbs: Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi.

- Dharana– Concentration on a specific point or object.

Dharana means concentration, or one-pointed focus of the mind on a single point or object. This does not imply a form of forceful mental control, but rather a gentle coaxing of the mind to focus on its highest goal. It is best if the object of concentration itself intrigues us; some people are naturally attracted to the flame of a candle, or the form of a deity.

Dhyana – Meditation.

Dhyana, or meditation, can be defined as the act of isolating the psyche from all objects, or of effortlessly focusing on only one object. In contrast while practicing dharana, the preliminary stage of concentration, some effort is involved, whereas in dhyana, meditation is effortless.

Sacred texts describe the difference between dharana and dhyana as the difference between pouring water, which has small bubbles in it and breaks in the flow, and of pouring oil, where the concentration is totally smooth with no interruptions. In dharana the mind flows towards an object in an interrupted fashion, with other thoughts intertwining, which briefly impede the concentration, whereas in dhyana the mind flows towards its chosen object without distraction.

For some practitioners, dhyana becomes a mental vacation where no objects at all are considered, and nothing but pure subjectivity remains. There is no external focal point, just pure being.

As we relax more and more into this kind of dhyana, all thoughts subside naturally. When this emptiness becomes natural and effortless, it will connect the practitioners with their all-embracing essence.

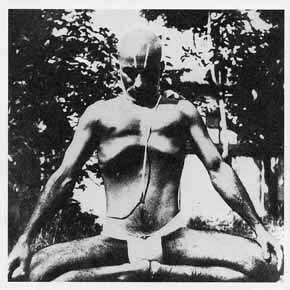

- Samadhi– Becoming one with the object of meditation.

In the state of samadhi we fuse with the objectivity. Individualized consciousness ends, and the yogi’s consciousness is discovered to be literally universal and collective. The small self falls away, and the true Self is permanently revealed.

The fourth section, Kaivalya Pada, is comprised of 34 sutras.

Kaivalya is sometimes translated as seclusion or isolation, but such a translation is insufficient to give the term its full meaning. From an occidental viewpoint, kaivalya is what psychologists call ‘individuation,’ a term describing a completely balanced mind, a state of complete detachment and wellbeing, in which the individual no longer depends on external factors to be happy and feel worthy. At this stage of evolution, practitioners will feel happy and secure no matter what situation they may find themselves in. The Kaivalya Pada describes total freedom from all mental concepts, including the sense of ‘I’ or ego. It also depicts the state of one who abides effortlessly in the transcendental Self. According to Patanjali, to be fully and permanently established in that Self is the goal of yoga.

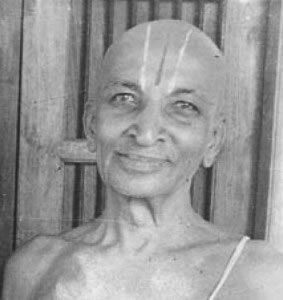

Sri Tirumali Krishnamacharya.

There are not too many things known about Krishnamacharya, since he was a humble man that only concerned with the present moment.

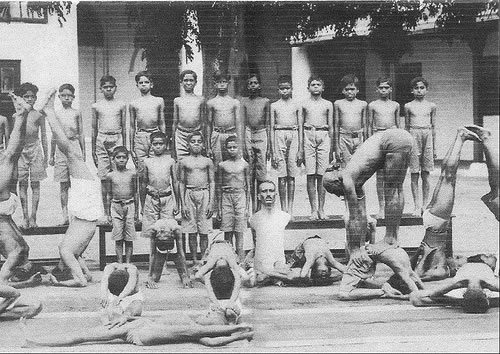

All we can say is that he was compelled to go to the Himalayas around 1916 to gain knowledge of Yoga. There he met his guru Rama Mohan Brahmachari, and spent seven and a half years in his company studying The Yoga Sutras.

At that time, he studied among other scriptures, the “Yoga Karunta” by heart, a mysterious document that supposedly was written on banana leaves.

Subsequently and after Krishnamacharya left his guru, more or less around 1926, he embarked on a search for the Yoga Karunta. After looking incessantly he lastly found it at the Calcutta University library. Immediately following the finding of this treasure, and because he realized that the book was badly injured by ants the story says that he transcribed it.

“Karunta” means “cluster” and it is believed that this manuscript, enclosed the sequences of Asana of the famous Mysore style of ashtanga yoga.

The “Yoga Karunta” is credited to the sage Vamana Rishi, who came to earth when Ashtanga Yoga was drifting into darkness.

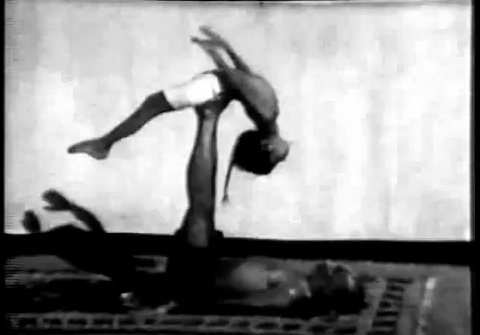

This book talks about executing asanas together with vinyasa and breathing.

This book talks about executing asanas together with vinyasa and breathing.

It states that the purpose of vinyasa is inner purification. Therefore it says that vinyasa in coordination with breath and bandhas, enhances blood distribution, mitigates pain and eradicates pollutants and ailments.

Drishti (gaze) is also contemplated in the book which states that while practicing asana, we can’t overlook and neglect the use of Drishtis (gaze), towards specific points in the physical body, these drishtis will keep the mind in the present moment and while it is a tool for concentration, it will also keep the eyes healthy and strong. There are nine dristhis: the nose, between the eyebrows, navel, thumbs, hands, feet, up, right side and left side. If the mind centers its attention solely on inhalation, exhalation, and drishtis, this concentration leads the mind to dhyana (meditation).

In psychology, there is a school that believes that by moving your eyes in certain directions you are able to unleash repressed emotions and memories from the brain.

In psychology, there is a school that believes that by moving your eyes in certain directions you are able to unleash repressed emotions and memories from the brain.

The Vedas. There are four Vedas: The Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvanaveda.

The first to be written was the Rigveda, which is believed to date back 8500 years BC. The Yajurveda follows some time later.

The Vedas contain details relevant information of certain Yoga movements done in conjunction with breath and mantras. As a matter of fact suryanamaskar A and B are described step by step, following the vinyasa method we use in the present.

The Aruna Mantra in the Yajurveda stipulates that the number of the Vinyasas for Suryanamaskara “A” which are nine, conversely the Rigveda instructs to intertwine the Saura Mantra that encloses 17 syllables with Suryanamaskara b, which has 17 venyasas, and so on and so forth.